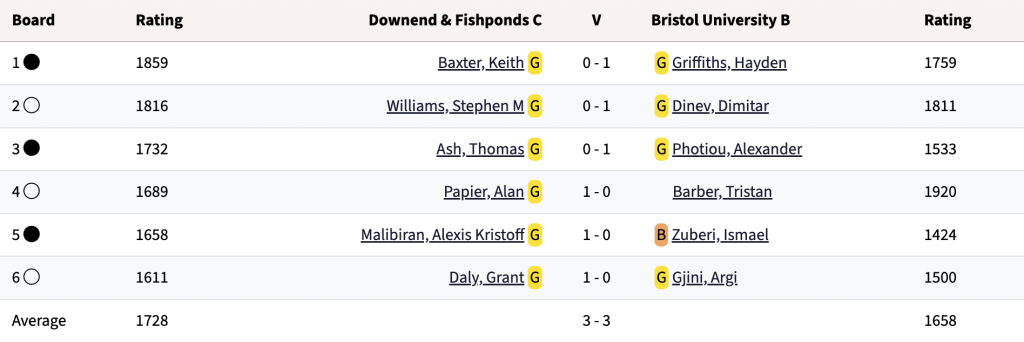

Our eleventh match of the season was an away match against Downend & Fishponds C on 5th March. Going into this match, I thought we had a realistic chance to draw or even win the match. However, we had a stronger team the last time we played Downend and we lost 2-4, so we were clearly still the underdogs. I’ll cover the games in the order that they finished.

Board 4

Tristan had Black on Board 4 and his game started with a Réti that quickly transposed into an Anti-Nimzo-Indian. White soon got an isolated c-pawn and Tristan proceeded to reroute all of his pieces to the queenside.

In the above position, the best line is the complicated tactical sequence 13. Nb5 Rxd3 14. Nxc7 Rxa3 15. Rd1, where White can temporarily give up a bishop because of the threat of mate on d8 and the fact that the rook on a8 is trapped. Instead, White played 13. c5, which attacks the knight on b6. Tristan responded with the natural 13… Nd5, moving the attacked knight, but Black can tactically defend the knight with 13… Nc6, which attacks the knight on d4. After 14. cxb6 Qxb6, the knight on d4 is pinned to the queen by the rook on d8, so, after 15. e3, the knight is won by 15… e5 and Black is doing decently, but of course this didn’t happen.

There are a couple of tactical sequences here that lead to objectively equal positions. Firstly, there’s 19… Ndxe2+ 20. Kh1 Rxd3 21. Nxa5, which wins a pawn for Black but it’s hard to evaluate the resulting position. Also possible is 19… Qxa3 20. Nxa3 Ndxe2+ 21. Qxe2 Nxe2+ 22. Kh1, which also wins a pawn for Black but White has some pressure with the bishop on g2. Instead, Tristan played 19… Qa4, which crucially leaves the rook on d8 undefended but threatens the devastating 20… Ndxe2+, so White played 20. Kh1. Then Tristan played 20… Rb8, which cleanly hangs the knight on c3 because 21. Nxe2 is no longer a check. However, White somehow missed this and played 21. e3.

The best way for Black to try to survive is with 21… Qc2 because the queen trade is forced if White wants to maintain the objective advantage, but Tristan instead hung the rook on d8 and mate in one with 21… Ndb5. White did not miss this, so the game unfortunately ended with 22. Qxd8#.

Board 6

Argi had Black on Board 6 and his game started with the Queen’s Gambit Declined.

White missed an opportunity to be much better here with 10. d5, which appears to hang the pawn at first glance, but it does not. After 10… exd5 11. exd5, the d5 pawn is not hanging to 11… Qxd5 because of 12. Bxh7+, winning the queen. In the game, White instead hung the d4 pawn with 10. Bf4, after which there’s simply 10… cxd4 11. cxd4 Nxd4. Despite this, White certainly had compensation due to Argi’s lack of space and development.

This soon changed, however, since White played the objectively losing 19. Qf4 here, which allows the devastating triple fork 19… Qa3, attacking both rooks and the bishop. After 20. e5, Black can take either the bishop or the rook on e7. There is in fact an argument to be made that taking the bishop leads to an easier-to-win position because 20… Qxe7 allows 21. Qe4, which both attacks the rook on a8 and threatens mate on h7.

In the above position, Argi made his move and resigned. I am told the official explanation for this is that he needed to use the lavatory, which would apparently have taken so long that he would have lost on time. Anyway, despite the hanging rook, Black has a forced win here. After 21… g6 22. Qxa8 Bb7 23. Qa7, there’s 23… Qg5, which wins the exchange because the rook on c1 is attacked and mate is threatened. Oh well.

Board 5

Ismail had White on Board 5 and his game started with the Grand Prix Attack in the Sicilian. He played some funny-looking opening preparation where White plays 6. f5 despite Black having pawns on e6 and g6.

White has a decision to make here: where should the bishop on c4 go? The best move is 10. Bb3 because there aren’t any tempo moves on the bishop and the bishop is better placed on its current diagonal. The issue with 10. Bb5 is that the bishop ends up locked out of the game after 10… Nd4 because of the simple plan of playing 11. a6 and 12. b5 to force the bishop to retreat. In fact, White must ensure that the bishop doesn’t get trapped after 13. c4. In the game, however, Black played 10… a6 and Ismail was given the additional option of 11. Bxc6 to no longer have to worry about the bishop. Black proceeded to expand on the queenside anyway with 15… b5, leaving Ismail with fairly little space.

The main critical moment of the game occurred after 20… Rf8. The best move is 21. Be3 because it prevents the infiltration 21… Rf2. After 21… d4, however, it looks like 21… Rf2 may still be a problem, but the awkward move 22. Nf1 holds everything together surprisingly well, and the rook can be forced off f2 with 23. Kg1 next move. Ismail instead played 21. Bd6, which attacks the rook and the c5 pawn, but Black has 21… Rf2, which counterattacks the c2 pawn. This put Ismail in a tricky position and he eventually lost a pawn as a result, which was certainly made worse by the fact that said pawn made it to the 2nd rank immediately.

The pawn on d2 proved so strong that there was no way for Ismail to stop it promoting without giving up a piece for it. Black finished the game off in style with the deflection tactic 28… Bxg2+, which forces 29. Rxg2, after which Black can simply promote, so Ismail resigned. With 3 consecutive losses, one could say that the match couldn’t have been going any worse, since winning the match was already impossible at this point. As a result, I was already resigned to the fact that we were going to lose the match, but of course you never know what might happen.

Board 2

Dimitar had Black on Board 2 and his game started with the Accelerated London System. Nothing crazy happened in the first 10 moves because, well, it’s the London, but that certainly didn’t last long.

When Dimitar played 10… c4, he was no doubt expecting 11. Be2 to be blitzed out, but White actually extremely dubiously sacrificed the bishop for 2 pawns with 11. Bxg6 fxg6 12. Qxg6+, which certainly left me confused when I glanced over a couple of minutes later. The sacrifices didn’t end there because White later temporarily sacrificed a bishop and sacrificed the exchange, both to open up Dimitar’s king. Dimitar was up a rook for 4 pawns when the engine started to scream at the top of its figurative lungs.

Dimitar lost all of his objective advantage here with the logical-looking 29… Nxd7 because of 30. Nc7+. If Black tries to escape the checks with 30… Ka7, White can prevent the king from escaping with 31. Nb5+ Ka6 32. Nc7+ Ka7. Therefore, Black must try 30… Kb8, but after 31. Nd5+ Qe5 32. Qxe5+ Nxe5, there’s the rook fork 33. Ne7. This leads to a rook, knight, and 2 pawns vs rook and 5 pawns endgame that the engine says is equal but it’s not so easy for a human to evaluate such an imbalanced position. In the game, White blundered back with 30. Nd6, attacking the rook on c8 and the b7 pawn. To avoid losing either, Dimitar played 30… Rb8, an objectively losing blunder because it boxes in the king on the a-file. The winning move is 31. Rb5, which threatens 32. Ra5#. The importance of moving the rook to the 5th rank specifically is that it prevents 31… Nc5 followed by 32… Na6 to shield the king. If the rook wasn’t on b8, Black would have the additional option of achieving this manoeuvre by playing 31… Nb8 or simply stopping a-file threats with the rook. Since 31… Rbd8 loses to 32. Ra5+ Kb8 33. Nf5+, which wins the queen and the knight for only a rook, Black’s best try is perhaps 31… b6. After 32. Qf3+ Ka7 33. Qd5, however, White is threatening the rook sacrifice 34. Ra5+ bxa5 35. Qxa5#, and White has too many threats against the king generally for Black to survive if White plays accurately. Anyway, the sequence of objective blunders continued because White played 31. e4 instead, which makes sense because it threatens 32. Qa3# but this can be easily prevented by 31… Nc5 to shield the king with 32. Na6.

Somehow, despite the fact that the material imbalance at this point was a rook for 3 pawns, the engine claims that the position is completely equal, although in this particular case that could not be any more misleading. After 32. Qa3+ Na6, White decided to sacrifice even more material with 33. Rxb7 Rxb7 34. Qxa6+, which left Dimitar up 2 rooks for a knight and 4 pawns. White had the option of entering a queen, rook, and pawn vs queen and 5 pawns endgame but declined to do so, so Dimitar smoothly converted his material advantage into an easily winning endgame, at which point his opponent resigned.

Board 3

Alex had White on Board 3 and his game started with the Andreaschek Gambit in the Sicilian, which I played myself against Alex’s opponent last term. No pieces were traded for a long time and Alex’s position ended up a bit cramped and uncomfortable.

While the engine claims that the above position is equal, it is unclear what White should do about the fact that the b2 pawn is hanging. Alex played 18. Nb1, which allows Black to win the b-pawn and, after 18… Bxb2 19. Rc2, give White doubled f-pawns.

However, Black decided not to play 19… Bxf3, and instead simply played 19… Bf6. There is an interesting line after 19… Bxf3 that requires some calculation, which is 20. Bxb2 Bxd1 21. Bxf7+ Nxf7 22. Rxb4 Nxb4 23. Nc3 Bc2. When the dust settles, the imbalance is 2 rooks and a knight for Black and a queen for White, so Black should be, and objectively is, winning. Anyway, going back to the game, Alex now had the initiative and his pieces sprung into action with a series of tempo moves 20. Bc5 Qf4 21. Be3 Qf5 22. Rc5, so Alex now appeared to be the one pressing.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, the best move here is 22… Be5, because, after 23. Nxe5 Nxe5 24. g4, while Black loses the bishop on h5 for 2 pawns, Black has at least a perpetual after 24… Bxg4 25. hxg4 Nf3+ 26. Kh1 Qxg4. In the game, Black opted for 22… Ne5. After 23. Nxe5, technically the best move is 23… Bxd1 but no human is finding all the best moves in the absurd line that follows so Black played 23… Bxe5. The difference between this and the previous line is that Black has no perpetual after 24. g4 Bxg4 25. hxg4 Qxg4+ because White can simply block the check with 26. Qg2 due to the now-conveniently-placed queen on f1. Soon after this, Alex won more material, and he eventually ended up smoothly converting an endgame where he had to avoid trading off his last pawn if he didn’t want to demonstrate the knight and bishop mate. With this excellent win, it was suddenly entirely down to me whether we would draw the match or not, but I needed to win for that to happen.

Board 1

I had White on Board 1 and my game started with the Alapin Sicilian. My opponent went for a rare gambit with 3… Nf6, but, unfortunately for my opponent, this didn’t get me out of prep.

I get this enough online to know that my preparation here is the rarely-played 4. Qa4+ Bd7 5. Qb3, which already leaves Black in a tricky position because the b7 pawn is attacked and the d5 pawn is defended because the bishop on d7 gets in the way of the queen. However, over the next dozen moves, my advantage dwindled as my opponent untangled and started pressing.

My position started to get rather unpleasant as I desperately needed to play d4 but various tactics were deterring me. In the above position, I wanted to force the queen off f4 with 19. Qc4 but that allows Black to sacrifice the rook on e2 for a bishop and a knight. I should have played the ugly move 19. Qc2 but I wanted to have the option of playing 20. Qc4, so I blundered horribly by defending the bishop with 19. Rc2. My opponent blitzed out 19… Bxf3 and I was confused because I had been wanting that for ages and the only way it would make sense is if I was blundering something. I was in fact blundering something: back-rank mate, so it’s fortunate that I hesitated to play 20. Bxf3. My only choice was to play the very weakening move 20. gxf3 and just try to survive. I proceeded to find all of the best moves and my opponent burnt a lot of time trying to find a surprisingly-elusive knockout. In rerouting the knights to the kingside to launch an attack against my king, my opponent had weakened the queenside so I eventually managed to win 2 pawns there. Since my opponent still hadn’t won back my d-pawn, this left me up 3 pawns, so I had objectively equalised and was suddenly playing for a win.

I thought my opponent had to play 28… Rd6 here, and that is correct because it’s hard for me to make a move. Apparently I have to play 29. Qc8 or 29. Qb4, which aren’t exactly obvious moves. With only a couple of minutes left on the clock, my opponent threatened mate on f2 with 28… Nxh3 but this loses because, after 29. Bd1, the rook on c2 prevents mate and the knight on h3 is pinned to the queen so neither piece can easily move. Now 29… Rd6 isn’t a problem because 30. Qc7 is very strong. Black wants to defend with 30… Qe7 but this would hang the knight on h3 now, so Black is dead lost. With only a matter of seconds on the clock, my opponent tried to get me to hang mate but I ended up doing the mating myself as I sacrificed my queen on e8 for back-rank mate.

Summary

Despite a rough 0-3 start on the bottom 3 boards, we pulled off a 3-0 finish on the top 3 boards to draw the match 3-3, our first draw of the season. In fact, we had some chances to even win the match considering there were 2 (nearly 3 but I caught myself) mate hangs. Nevertheless, this draw helps a lot, as, assuming Clevedon lose their remaining 2 matches, which is far from guaranteed, beating Yate would be sufficient to not get relegated because our tiebreaks are good compared to Clevedon’s. Before that pivotal match against Yate, however, there are still 2 matches where we could theoretically pick up points so we shall see if we can do that. Our next match will be a fun one, as it is a home match against Bristol Grendel A on 20th March, so the next match report will be posted soon after that.